-

In Focus: Alan Stanners

-

-

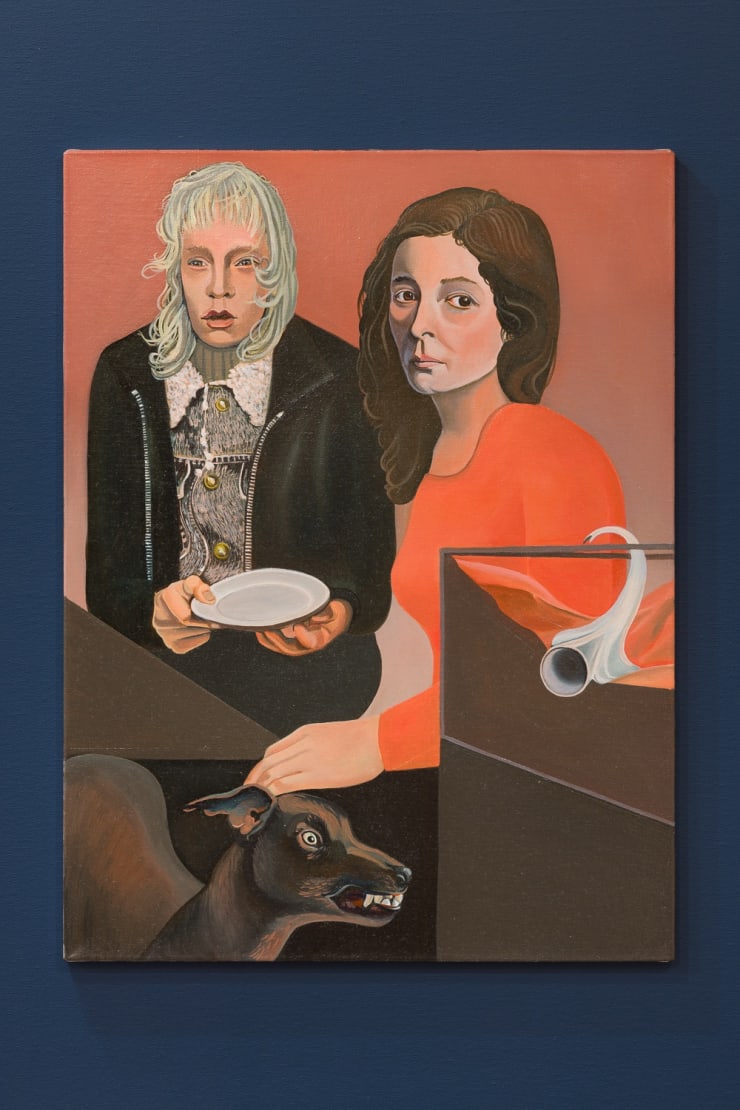

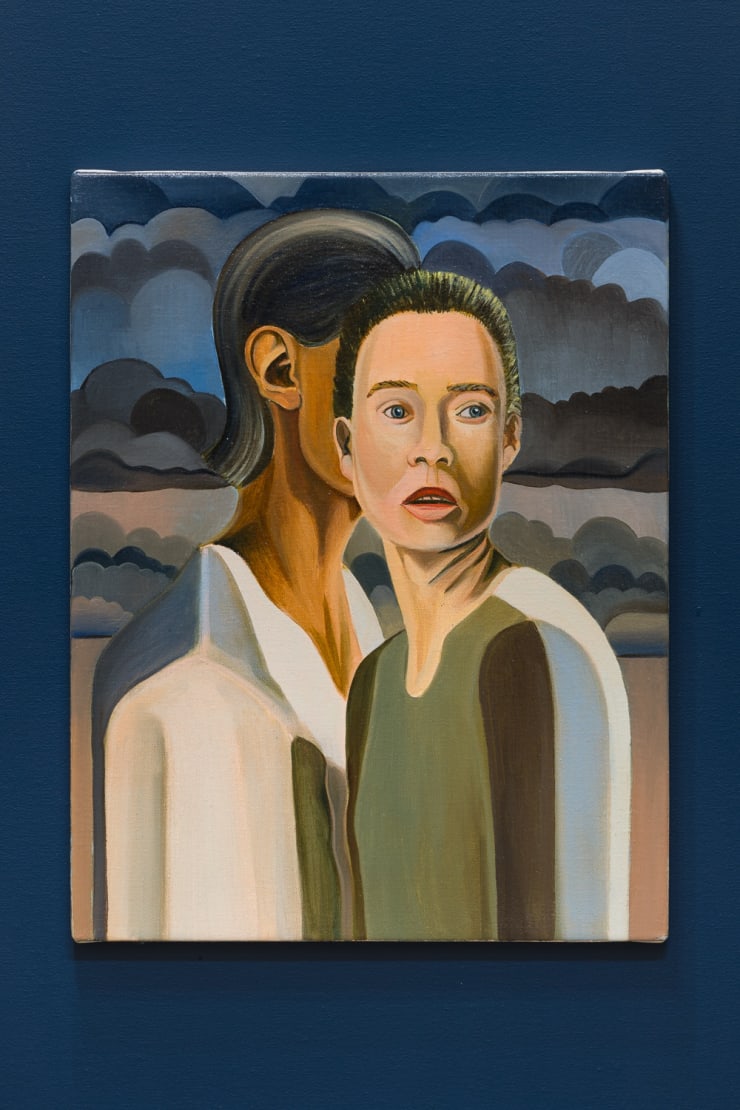

Unknown figures gaze passively out of Stanners' paintings, on their own or occasionally in pairs - their positioning intimate - occupying one anothers personal space as neither figure acknowledges the other - their focus rests elsewhere. Their disinterested, acquiescent relationship with one another is disquieting as we wonder who they might be, strangers, lovers or siblings.

In all of his paintings, there is an uneasiness, something out of place or not quite right; an awkwardly held hand, a mouth that rests unnaturally slack allowing food to spill out, or an unfamiliar object positioned with apparent significance. Moments break the spell cast by these seductive paintings, allowing us the distance to reconsider and reassess our first impressions. Stanners' handling of paint shifts from painting to painting and even within the same work, sliding from stylised, crystal clear representation to looser flowing brushwork that seems to indulge in the feeling of the paint. The sense we get is that his portraits are less about depiction and more a framework on which he can hang his ongoing exploration of otherness.

-

We spoke with Alan Stanners to discuss the development of his practice from abstraction through to portraiture, and how these two approaches aren’t as different as they might first seem. We discuss relationship with the written work and how that has come in and out of his practice over the years, and he speaks about the sense of “otherness” which pervades all of his work.

Five or six years ago there was a fairly dramatic shift in your practice, from an intellectual abstraction to more representative painting and, in particular, portraiture. Would you like to tell us what provoked this move and what relationship you feel that these two chapters of your work have with one another?

On appearance there definitely was a shift moving from abstraction to figuration however I don’t necessarily see these differing approaches as being radically dissimilar from each other. In both cases, I have applied similar efforts of creative judgment and curiosity, however, I think when I was younger the transgressive possibilities of end-game era Painting offered me an opportunity to produce very energetic work, tackling my perceptions of the world with broad anarchic stokes. As I’ve gotten a little older, figuration has allowed me to slow down and deal with things in a more nuanced way.

I think a need for greater artistic clarity was another important influence on the shift. I found that working abstractly, despite whatever ideas or narrative ambitions I had, the audience for my work never seemed to see the work as anything other than commentary about Art or artists, or the history of Art and Paintings’ place within it. Although I do care about Art, I’m really more interested in human stories and painting gives me an interesting medium through which to think about the world. Working figuratively has also helped me to better steer the conversation around my ideas.

-

-

As previously mentioned, your current practice focuses predominantly on portraiture. From where do you draw these characters? Do they have lives beyond your paintings? And are there particular characters who reappear?

Despite the portraits’ realist appearance, I think of them in more abstract or non-realist terms. The realism is just a stylistic means to an end to give the painting form and a language to play with. I feel the true subject is the emotional tone, tension and atmosphere of the image. I think of them as portraits of psychological moods. Mostly I want all the expressivity to exist in the making of the image, rather than its identity as a painted object.

The portraits are all imagined fictions and none come from one place or inspiration, they all have multiple influences, much like real people. I often start with a vague conception of what I’d like it to become, a pose in a magazine could trigger something or whilst reading a paragraph in a book I’ll wonder what that would look like. Perhaps I’ll develop something from a purely imagined sketch or a collage of different paintings I like. Often for practical reasons, a friend might pose for me, to study the way the body acts and how light defines it. It's incredibly hard to imagine everything, it would be too painstaking.

The portraits are in a constant state of change as they develop over weeks and months, with colour, composition and expression never certain until I decide to stop working on them. My studio is located in my home, so I live alongside them and they are subject to the same experiences and frustrations that I am. -

-

There is often an uneasiness or uncanniness to your paintings, a sense of something out of place or not quite right that pulls us back for multiple viewings. To what do you account feeling and how conscious of it are you when planning and painting?

I’m glad this comes across, as it’s really the focus of my work. Persistent themes such as humanities’ relationship with itself and the natural world and the otherness found in the banalities of the everyday, offer lots of scope to literalise a sense of uncanniness and unease. I also deliberately toy with the viewer in the work, despite the apparent realism, often shadows and highlights are inconsistent, proportions are skewed and perspectives are exaggerated. I think this tells our rational brain that superficially everything looks ok, whilst emotionally we know something's subliminally wrong. I have always been fascinated by Rene Magritte and the surrealist strategy of using simulacra that appear to create the illusion of contact with the real but are actually a window into the void.

-